![]()

By tfawcus

.jpg) Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.

Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.

| Author Notes |

Setting: Kalynorad, a fictitious town near the battlefront in Eastern Ukraine

Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bucha_main_street,_2022-04-06_(0804).jpg is used here under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license. It is used generically and not intended to suggest a specific setting for this fictional story. British English is used throughout. (e.g. leant instead of leaned, single inverted commas for speech, etc.) |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes | Written in British English. |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

The Sharp Quill challenge was to write a piece that explores the unseen forces that bind people, events, or moments together. This might be emotional, psychological, spiritual, or something more abstract. Word limit: 750-1,200 words (Actual Word Count: 1193).

Image: Photo by Patrick Hendry on Unsplash. |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes | 900 words |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

British English spelling and writing conventions are used throughout.

Photo by Ronan Hello on Unsplash |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes | Photo by Wyxina Tresse on Unsplash |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Photo by Arthur A on Unsplash

British English spelling and grammar Thank you for reading and reviewing. Honest, constructive criticism welcomed. |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

British English spelling and grammar.

Thank you for reading and reviewing. I welcome honest, constructive criticism. Photo by Valerie Sidorova on Unsplash. |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Characters

Dmitri, a teenage boy recovering from catatonia (a state in which someone is awake but does not seem to respond to other people and their environment). Mira, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena, a volunteer carer looking after Dmitri and aiding his recovery. Leila, a foreign girl employed by Elena. Setting: Somewhere in Central Europe. British English spelling and grammar used throughout. Thank you for reading and reviewing. I welcome honest, constructive criticism. Photo by Rahul Pugazhendi on Unsplash. |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Characters

Dmitri, a teenage boy recovering from catatonia (a state in which someone is awake but does not seem to respond to other people and their environment). Mira, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena, a volunteer carer looking after Dmitri and aiding his recovery. Leila, a foreign girl employed by Elena. Pavla Miret, an art teacher. Setting: Somewhere in Central Europe. British English spelling and grammar are used throughout. Thank you for reading and reviewing. I welcome honest, constructive criticism. |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Characters

Dmitri, a teenage boy recovering from catatonia (a state in which someone is awake but does not seem to respond to other people and their environment). Mira, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena, a volunteer carer looking after Dmitri and aiding his recovery. Leila, a foreign girl employed by Elena. Pavla Miret, an art teacher. Setting: Somewhere in Central Europe. British English spelling and grammar are used throughout. Thank you for reading and reviewing. I welcome honest, constructive criticism. |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Characters

Dmitri, a teenage boy recovering from catatonia (a state in which someone is awake but does not seem to respond to other people and their environment). Mira, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena, a volunteer carer looking after Dmitri and aiding his recovery. Leila, a foreign girl employed by Elena. Pavla Miret, an art teacher. Setting: Somewhere in Central Europe. British English spelling and grammar are used throughout. Thank you for reading and reviewing. I welcome honest, constructive criticism. Image by Andrey Shishkin, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution license. |

![]()

By tfawcus

.jpg)

| Author Notes |

Footnote: tenir la chandelle is a French expression meaning 'to hold the candle'. It refers to the awkward situation of being alone with a couple, feeling like you shouldn't be there. The expression originates from a time before electricity, when couples would require someone to hold a candle to provide light during romantic moments, often making the candle holder feel like an unwelcome third party. (I hope that throws some light on things!)

Characters Dmitri, a teenage boy recovering from catatonia (a state in which someone is awake but does not seem to respond to other people and their environment). Mira, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena, a volunteer carer looking after Dmitri and aiding his recovery. Leila, a foreign girl employed by Elena. Pavla Miret, an art teacher. Andriy Kolt, an army major. Setting: Somewhere in Central Europe. British English spelling and grammar are used throughout. Thank you for reading and reviewing. I welcome honest, constructive criticism. Image: The Kiss, by Francesco Hayez 1859 |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Footnote: The Ukrainian kopiyka is a small denomination coin equivalent to the Russian kopek

Lanch-bak is a misspelling of "lunch bag." The term is used in the context of lunch bags with Ukrainian themes, often decorated with the Ukrainian flag or other patriotic symbols Characters Dmitri, a teenage boy recovering from catatonia (a state in which someone is awake but does not seem to respond to other people and their environment). Mira, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena, a volunteer carer looking after Dmitri and aiding his recovery. Leila, a foreign girl employed by Elena. Pavla Miret, an art teacher. Andriy Kolt, an army major. Setting: Somewhere in Western Ukraine, in the Carpathian Mountains. British English spelling and grammar are used throughout. Thank you for reading and reviewing. I welcome honest, constructive criticism. Photo by Alireza Zarafshani on Unsplash |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Footnote: Kvass is a popular Eastern European drink made from stale rye bread.

Characters Dmitri, a teenage boy recovering from catatonia (a state in which someone is awake but does not seem to respond to other people and their environment). Mira, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena, a volunteer carer looking after Dmitri and aiding his recovery. Leila, a Syrian girl employed by Elena. Pavla Miret, an art teacher. Andriy Kolt, an army major. Mykola Doroshenko (Myko), proprietor of Baba Roza's cafe in Velinkra Nadia, his daughter Setting: Velinkra, a fictitious small town in Western Ukraine, in the Carpathian Mountains. British English spelling and grammar are used throughout. Thank you for reading and reviewing. I welcome honest, constructive criticism. Photo by Toby Do on Unsplash |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Characters

Dmitri, a teenage boy recovering from catatonia (a state in which someone is awake but does not seem to respond to other people and their environment). Mira, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena, a volunteer carer looking after Dmitri and aiding his recovery. Leila, a Syrian girl employed by Elena. Pavla Miret, an art teacher. Andriy Kolt, an army major. Mykola Doroshenko (Myko), proprietor of Baba Roza's cafe in Velinkra Nadia, his daughter Setting: A hunting lodge in the Carpathian Mountains. British English spelling and grammar are used throughout. Thank you for reading and reviewing. I welcome honest, constructive criticism. Photo by Klugzy Wugzy on Unsplash |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Characters

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy recovering from catatonia (a state in which someone is awake but does not seem to respond to other people and their environment). Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena Prishtina, a volunteer carer looking after Dmitri and aiding his recovery. Leila, a Syrian girl employed by Elena whom Dmitri has fallen in love with. Pavla Miret, an art teacher. Andriy Kolt, an army major. Fedir, his faithful retainer Ruslan Borodin, the Mayor of Velinkra Setting: Major Andriy's ancestral home on the outskirts of Velinkra (a fictional town in the Carpathian Mountains) British English spelling and grammar are used throughout. |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Characters

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy recovering from catatonia after the death of his twin sister in a bombing. Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena Prishtina, a volunteer carer looking after Dmitri and aiding his recovery. Leila, a Syrian girl employed by Elena whom Dmitri has fallen in love with. Pavla Miret, an art teacher who has been giving Dmitri lessons. Andriy Kolt, an army major who Dmitri and Leila rescued when he fell fom his horse Fedir, his faithful retainer Ruslan Borodin, the Mayor of Velinkra Olena, his wife Dr and Mrs Savchenko (Viktor and Nadia), recent arrivals in Velinkra Illustration by Art Pixel AI Images |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Characters

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy recovering from catatonia after the death of his twin sister in a bombing. Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena Prishtina, a volunteer carer looking after Dmitri and aiding his recovery. Leila, a Syrian girl employed by Elena whom Dmitri has fallen in love with. Pavla Miret, an art teacher who has been giving Dmitri lessons. Andriy Kolt, an army major who Dmitri and Leila rescued when he fell fom his horse Fedir, his faithful retainer Ruslan Borodin, the Mayor of Velinkra Olena, his wife Dr and Mrs Savchenko (Viktor and Nadia), recent arrivals in Velinkra Setting: On the outskirts of Velinkra, a town in the Carpathian Mountains, in Western Ukraine Image by ChatGPT |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Author note: The full idiom is 'cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass monkey'.

Not as rude as it sounds though. The phrase is thought to have originated from a time when cannonballs were stored on ships using a brass tray, and the contraction of the brass in freezing temperatures could cause the cannonballs to fall out. (Explanation requested by a reviewer). Characters Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy recovering from catatonia after the death of his twin sister in a bombing. Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena Prishtina, a volunteer carer who looked after Dmitri, aiding his recovery. Leila, a Syrian girl employed by Elena whom Dmitri has fallen in love with. Pavla Miret, an art teacher who has been giving Dmitri lessons. Andriy Kolt, an army major on home leave |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Characters

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy recovering from catatonia after the death of his twin sister in a bombing. Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena Prishtina, a volunteer carer who looked after Dmitri, aiding his recovery. Leila Haddad, a Syrian girl employed by Elena whom Dmitri has fallen in love with. Pavla Miret, an art teacher who has been giving Dmitri lessons. |

![]()

By tfawcus

.jpg)

| Author Notes |

Characters

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy recovering from catatonia after the death of his twin sister in a bombing. Mira Zahir, his twin sister, killed in a bomb attack. Elena Prishtina, a volunteer carer who looked after Dmitri, aiding his recovery. Leila Haddad, a Syrian girl employed by Elena whom Dmitri has fallen in love with. Pavla Miret, an art teacher who has been giving Dmitri lessons. Image: Jorge Jescar from Australia, CC BY 2. |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Note: I have a busy week ahead. Chapter Twenty-Four may be a while in coming.

Characters Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy recovering from catatonia after the death of his twin sister in a bombing. Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena Prishtina, a volunteer carer who looked after Dmitri, aiding his recovery. Leila Haddad, a Syrian girl employed by Elena whom Dmitri has fallen in love with. Pavla Miret, an art teacher who has been giving Dmitri lessons. Oleh, a guitarist that Dmitri met on the train from Lviv. Photo by Nadzeya Matskevich on Unsplash |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Characters

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy desperately chasing after the love of his life. Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Leila Haddad, a Syrian girl with whom Dmitri has fallen in love. Oleh, a guitarist that Dmitri met on the train from Lviv. Image: Detail from a public domain photograph of the Bohdan Khmelnytsky Monument in Kyiv. |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy trying to reach the love of his life.

Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena Prishtina, a volunteer carer who looked after Dmitri during his recovery from catatonia. Leila, a Syrian girl Dmitri fell in love with. Pavla Miret, an art teacher who gave Dmitri lessons. Andriy Kolt, an army major. Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy trying to reach the love of his life.

Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena Prishtina, a volunteer carer who looked after Dmitri during his recovery from catatonia. Leila, a Syrian girl Dmitri fell in love with. Pavla Miret, an art teacher who gave Dmitri lessons. Andriy Kolt, an army major. Image: Ruzena Maturova as the first Rusalka. This work is in the public domain. |

![]()

By tfawcus

Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.

Warning: The author has noted that this contains the highest level of violence.

| Author Notes |

Main Characters:

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy trying to reach the love of his life. Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena Prishtina, a volunteer carer who looked after Dmitri during his recovery from catatonia. Leila, a Syrian girl Dmitri fell in love with. Pavla Miret, an art teacher who gave Dmitri lessons. Andriy Kolt, an army major. Photo by Cristina Glebova on Unsplash |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Main Characters:

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy trying to reach the love of his life. Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena Prishtina, a volunteer carer who looked after Dmitri during his recovery from catatonia. Leila Haddad, a Syrian girl Dmitri fell in love with. Pavla Miret, an art teacher who gave Dmitri lessons. Andriy Kolt, an army major. Image: Oberon, Titania and Puck with Fairies Dancing. William Blake. c.1786 (A Public Domain work of art) |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Main Characters:

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy trying to reach the love of his life. Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena Prishtina, a volunteer carer who looked after Dmitri during his recovery from catatonia. Leila Haddad, a Syrian girl Dmitri fell in love with. Pavla Miret, an art teacher who gave Dmitri lessons. Andriy Kolt, an army major. Fedir, his faithful retainer Oksana (Ocky) Kovalchuk, his cook Hrytsko and Klym, a local poacher and his dog Image in the Public Domain. |

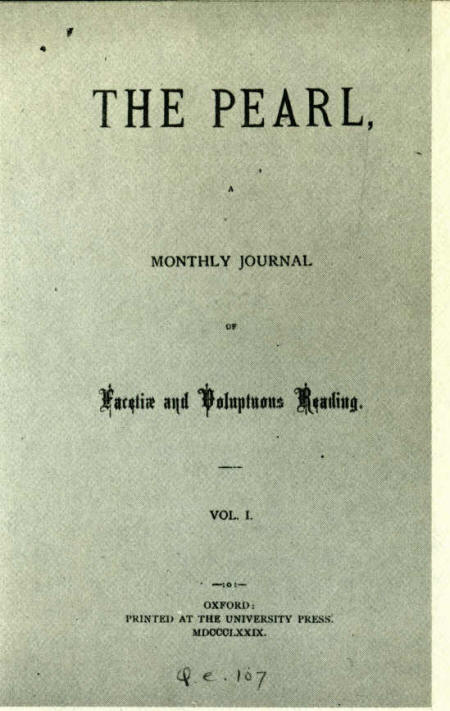

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Main Characters:

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy trying to reach the love of his life. Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena Prishtina, a volunteer carer who looked after Dmitri during his recovery from catatonia. Leila Haddad, a Syrian girl Dmitri fell in love with. Pavla Miret, an art teacher who gave Dmitri lessons. Andriy Kolt, an army major. Fedir, his faithful retainer Oksana (Ocky) Kovalchuk, his cook Hrytsko and Klym, a local poacher and his dog Image: 1879 The Pearl title page from Wikipedia - Public Domain. |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Main Characters in the Chapter:

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy trying to reach the love of his life. Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena Prishtina, a volunteer carer who looked after Dmitri during his recovery from catatonia. Leila Haddad, a Syrian girl Dmitri fell in love with. Pavla Miret, an art teacher who gave Dmitri lessons. Oleh, a guitarist that Dmitri met on his way to Kyiv |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Main Characters in this Chapter:

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy hellbent on reuniting with Leila, his true love. Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Elena Prishtina, a volunteer carer who looked after Dmitri during his recovery from catatonia. Leila Haddad, the Syrian girl Dmitri has fallen in love with. Oleh, a guitarist that Dmitri met on his way to Kyiv AI-generated image |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Main Characters in this Chapter:

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy hellbent on reuniting with Leila, his true love. Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Leila Haddad, the Syrian girl Dmitri has fallen in love with. Oleh Zhukov, a guitarist that Dmitri met on his way to Kyiv Lieutenant Sergei Hrytsenko, the POW camp commandant Viktor Karpov, a corporal in the Ukrainian army The Interrogator, a Ukrainian army colonel FS AI-generated image |

![]()

By tfawcus

| Author Notes |

Main Characters mentioned in this Chapter:

Dmitri Zahir, a teenage boy hellbent on reuniting with Leila, his true love. Mira Zahir, his twin sister, who was killed in a bomb attack. Leila Haddad, the Syrian girl Dmitri has fallen in love with. Oleh Zhukov, a guitarist that Dmitri met on his way to Kyiv Colonel Vadym Melnyk, a Ukrainian interrogator Major Andriy Kolt, an army major who knew Dmitri from Velinkra Lieutenant Sergei Hrytsenkothe POW Camp Commandant Corporal Viktor Karpov a prison guard in the Ukrainian army |

|

You've read it - now go back to FanStory.com to comment on each chapter and show your thanks to the author! |

![]()

| © Copyright 2015 tfawcus All rights reserved. tfawcus has granted FanStory.com, its affiliates and its syndicates non-exclusive rights to display this work. |

© 2015 FanStory.com, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Terms under which this service is provided to you. Privacy Statement